The Rebellious Roots Mother's Day

Mother’s Day began with women who fought slavery, war, and disease — and believed mothers had a public duty to shape a more just society.

Before it was about brunch reservations and a rush on carnations, Mother’s Day was a call to arms — or more accurately, a call to lay them down.

The roots of this holiday run far deeper than greeting cards and breakfast in bed. Mother’s Day began as a demand for peace, a cry for justice, and a public reckoning with war, loss, and the power of women to shape the world their children would inherit. Its founders, plural, didn’t see motherhood as sentimental. They saw it as moral authority. And they believed that with it came the obligation to build a more just society.

Julia Ward Howe’s Mother’s Day for Peace

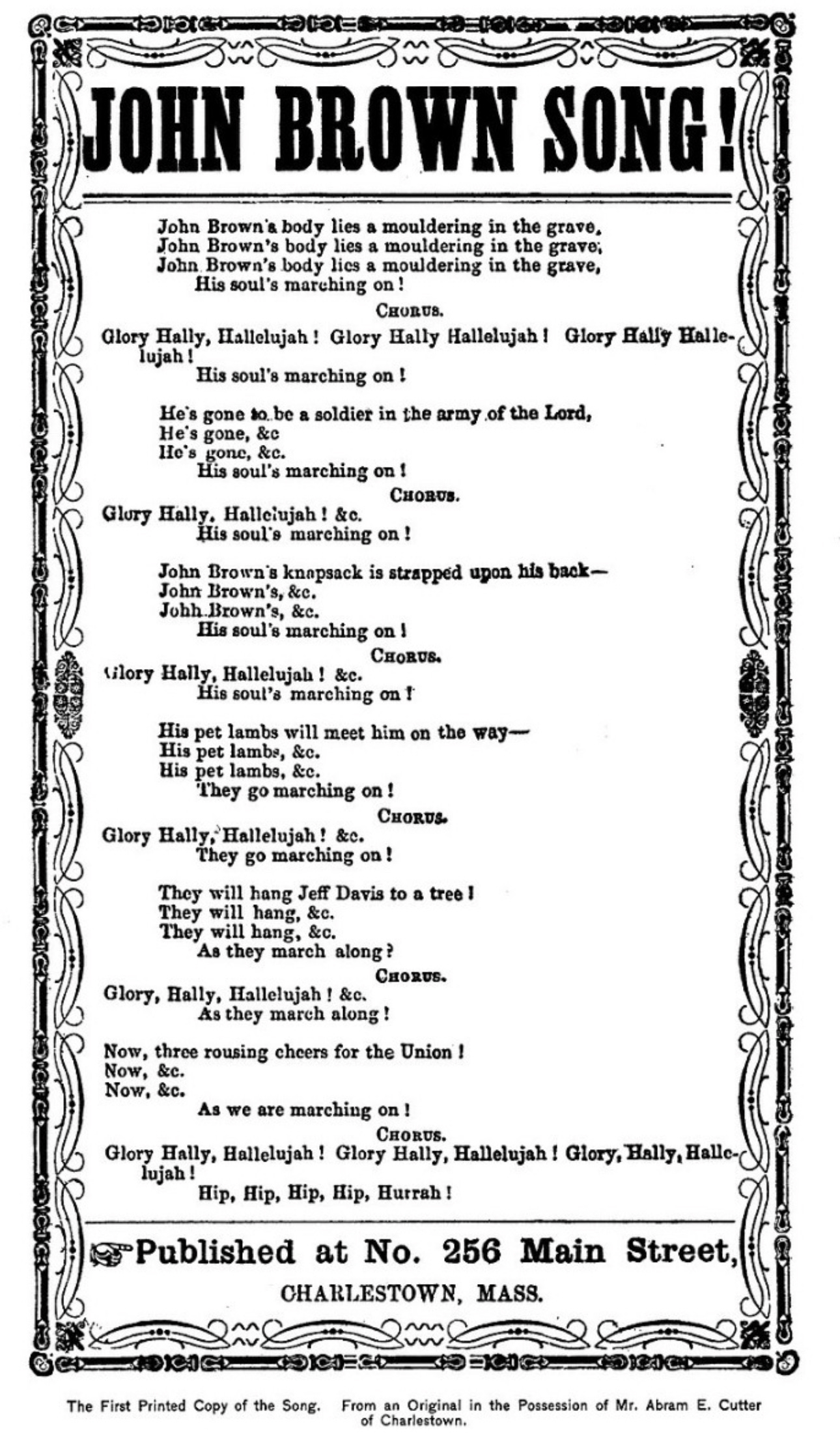

In 1870, Julia Ward Howe — a fierce abolitionist, suffragist, and the woman who wrote The Battle Hymn of the Republic — issued a bold “Mother’s Day Proclamation.” The hymn itself was a rewrite of the marching song John Brown’s Body, honoring the radical abolitionist executed for his armed uprising against slavery. Howe’s politics were clear. She saw slavery, war, and women’s subjugation as interlocking systems of injustice, and believed mothers had a moral duty to resist them all.

Her plea, titled Appeal to Womanhood Throughout the World, was written in the wake of the U.S. Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War. It was not about celebrating motherhood as domestic virtue. It was about women rising up to reject violence, nationalism, and the normalization of endless war. She envisioned a day when mothers of all nationalities would come together across borders to say: enough. No more sending our sons, or anyone’s sons, off to die for the ambitions of men.

For several years, she held “Mother’s Day for Peace” gatherings in Boston. They were public, political, and profoundly radical for their time. But they didn’t take root nationally at the time.

Ann Reeves Jarvis and the Politics of Reconciliation

Parallel to Howe’s organizing was another woman, less widely remembered but equally foundational: Ann Reeves Jarvis. In the 1850s, she founded “Mother’s Day Work Clubs” in Appalachia to improve health and hygiene in underserved communities. Her focus was practical: saving lives through clean water, sanitation, and education for mothers.

During the Civil War, those clubs tended to soldiers from both sides, Union and Confederate.

After the war, in 1868, she organized a Mother’s Friendship Day, bringing together families who had fought on opposite sides of the conflict. It was an act of radical reconciliation, grounded in the belief that mothers could mend what war had broken.

Anna Jarvis: Love, Loss, and the Fight to Remember

Ann Reeves Jarvis’s daughter, Anna Jarvis, carried the torch.

When her mother died in 1905, Anna vowed to fulfill one of her final wishes — that there be a day set aside to honor the sacrifices mothers make every day. In 1908, she held the first formal Mother’s Day service at a Methodist church in Grafton, West Virginia, and sent white carnations, her mother’s favorite flower, to attendees.

Her vision was not civic or commercial. It was intimate and sacred. But critics saw her as naive in trying to separate the personal from the political, a move that inevitably led to it being stripped of the very power her mother and Julia Ward were fighting to mobilize.

Anna insisted on the singular possessive: Mother’s Day, not Mothers’ Day. It wasn’t about celebrating motherhood in general. It was about honoring your mother, personally and privately.

She wrote thousands of letters, gave speeches, and eventually persuaded Congress to make Mother’s Day a national holiday in 1914.

But almost immediately, she saw it being hijacked.

A Holiday Co-opted

Florists, greeting card companies, and retailers jumped at the chance to turn reverence into revenue. The sentimentalism ramped up. The moral message faded out.

Anna Jarvis was horrified. She spent the rest of her life fighting the commercial takeover of Mother’s Day. She boycotted, protested, sued. She once crashed a luncheon where carnations were being sold to raise money for charity and was arrested for disturbing the peace.

She died in 1948, penniless and nearly forgotten, having watched the holiday she created turn into the very thing she loathed. And yet, her legacy endures, as does her warning.

So, Where Does That Leave Us?

Today, many of us mark the second Sunday in May by gathering with family, being treated or treating our moms to something special, or reflecting on the women who raised us. And we should celebrate mothers who provided love, labor, and guidance in our lives. But we can also use this moment to remember that motherhood can be a public force. And that honoring mothers meant more than giving them flowers. It meant heading their calls for justice, peace, and dignity for all.

I’m reminded of an interview I did recently with Melissa Ryan of

She spoke of the importance of community connection in ways that aren’t singularly political, including creating bonds with other mothers, in ways that will inevitably lead to conversation to connect and understand first, not just persuade.

So yes, enjoy the brunch. Savor the day.

But let’s also remember the origin story that rarely gets told, and that we celebrate by using our voices as mothers with courage to shape the world.

#MomsRising

Wow, thanks for that proud history. I am all for.... "Arise then all women of this day"!

Wonderful, thank you!

I found you thru Greg Olear and Stephanie Koff on the 5/8 on youtube. I saw one of your new venture with Lisa Graves called the 5/8 1/2- LOVE IT! I have only watched one but love the dynamic between you two, and the smart serious funny commentary is the best!