“The power of just mercy is that it belongs to the undeserving. It’s when mercy is least expected that it’s most potent—strong enough to break the cycle of victimization and victimhood, retribution and suffering. It has the power to heal the psychic harm and injuries that lead to aggression and violence, abuse of power, mass incarceration.”

― Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy

I remember as a teen when a girl from my high school almost knocked my mother down a flight of stairs, jostling past her carelessly on the steps at the mall. My hand was on her throat in a millisecond, and I could tell from her face that she saw murder in my eyes.

I grew up on the same diet of revenge fantasy as everyone else, cheering when the villain got their brutal comeuppance. We all celebrated, even as it contradicted the very bedrock of the faiths we claimed to follow.

I remember in the 1988 U.S. presidential election when Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis was asked by CNN anchor Bernard Shaw:

“Governor, if Kitty Dukakis [your wife] were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?”

Dukakis, a steadfast opponent of capital punishment, responded calmly:

“No, I don’t, Bernard. And I think you know that I’ve opposed the death penalty during all of my life.”

His response was widely criticized as technocratic and detached, and many believe it contributed significantly to his loss to George H.W. Bush.

Perhaps the response would have been different had he answered this way:

“I’d want 20 minutes alone with him in a room with no windows and a door that locks from the inside. I’d want to inflict as much pain on that monster as possible before the life drained out of his eyes. That is what the husband in me would want, and I imagine that’s what many grieving the brutal loss of a loved one would give anything for. That is revenge. But our system is about justice, not vengeance. There is a reason we don’t let the grief-stricken survivors decide the case, the fate, or inflict the punishment.

As president, the question isn’t, would I, as a man, want to seek vengeance? It’s will I, as president, uphold justice? Will I stay true to my values and the principles enshrined in the Constitution’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment? As president, I will. ”

This response would have acknowledged the human thirst for vengeance while elevating the conversation to the principles of justice and fairness. But in a nation that professes faith but worships guns-even more now than in the 1980s- no answer short of bloodlust might assuage the fearful masses.

The Death Penalty Is Wrong

The death penalty is wrong for several reasons—moral, ethical, practical, and systemic.

Taking a life as punishment is state-sanctioned violence and lowers society to the same level as the crime being punished. Instead of seeking justice, it often perpetuates a cycle of violence and retribution, which doesn’t truly address harm or promote healing.

The death penalty denies the offender the opportunity for redemption. Even those who commit heinous crimes are capable of transformation, and justice systems should reflect values of rehabilitation and mercy, not finality and revenge.

Across most faiths, there has been a growing movement toward rejecting state-sanctioned killing, particularly in contexts where it reflects systemic injustice or risks wrongful execution. This shift is often driven by faith-based advocacy for human rights, justice reform, and the belief in redemption.

It is astonishing the number of times people who profess to be followers of Jesus Christ ignore the most central teaching of the gospel. Jesus didn’t just teach about forgiveness and mercy—he demonstrated it in the most extraordinary way. In the middle of his own state-sanctioned execution, he prayed for the very people carrying it out: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). That act wasn’t just an idea or a moral suggestion—it was a radical commitment to the principles of mercy and forgiveness, even in the face of unspeakable injustice.

For those who claim Christianity, his teachings on forgiveness are clear. He equated anger and hatred with murder in the heart (Matthew 5:21-22) and rejected limits on forgiveness, saying not seven times but seventy-seven times (Matthew 18:21-22). His life and death didn’t leave room for vengeance; instead, they called for reconciliation and mercy as central to living a life of faith.

If forgiveness is so central to his example, what does it mean to claim Christianity while rejecting the call to show that same mercy, even when it’s hard?

The State Murders Innocents People

The death penalty is irreversible. There’s no way to correct the error if an innocent person is executed, and wrongful convictions happen more often than most people realize. Since 1973, over 190 people in the U.S. have been exonerated after being sentenced to death, showing how flawed the system can be. One of the most tragic cases is that of Cameron Todd Willingham, who was executed in Texas in 2004 despite significant evidence suggesting his innocence.

The Cost of Revenge

Beyond morality, there’s also a financial argument. Studies show the death penalty costs significantly more than life imprisonment without parole due to lengthy trials, appeals, and the complex requirements of capital cases. For example, California has spent over $4 billion on the death penalty since 1978 while executing only 13 people. That money could instead fund victim support programs or community safety initiatives.

Justice Unevenly Served is Not Justice

The inequities of wealth, race, and status in the application of the death penalty undermine its legitimacy.

Disproportionate Impact on Black Americans: In the United States, Black defendants are significantly more likely to receive the death penalty, particularly when the victim is white. Studies consistently show that race plays a major role in sentencing outcomes, revealing a justice system that disproportionately targets people of color.

The Cost of Inadequate Defense: Defendants who cannot afford private legal counsel often rely on overburdened public defenders who lack the time and resources to mount an adequate defense. Wealthier defendants rarely face these obstacles, illustrating how money and privilege can spare someone from the ultimate punishment.

Lack of Deterrence

Finally, it’s not an effective deterrent. Studies consistently show that the death penalty doesn’t significantly reduce violent crime rates compared to states or countries without it. A 2021 study from the Death Penalty Information Center confirmed that murder rates are consistently higher in states that use the death penalty compared to those that do not. Life imprisonment without parole achieves the same goal of protecting society without crossing the moral line of taking a life.

The Politics of Forgiveness and Redemption

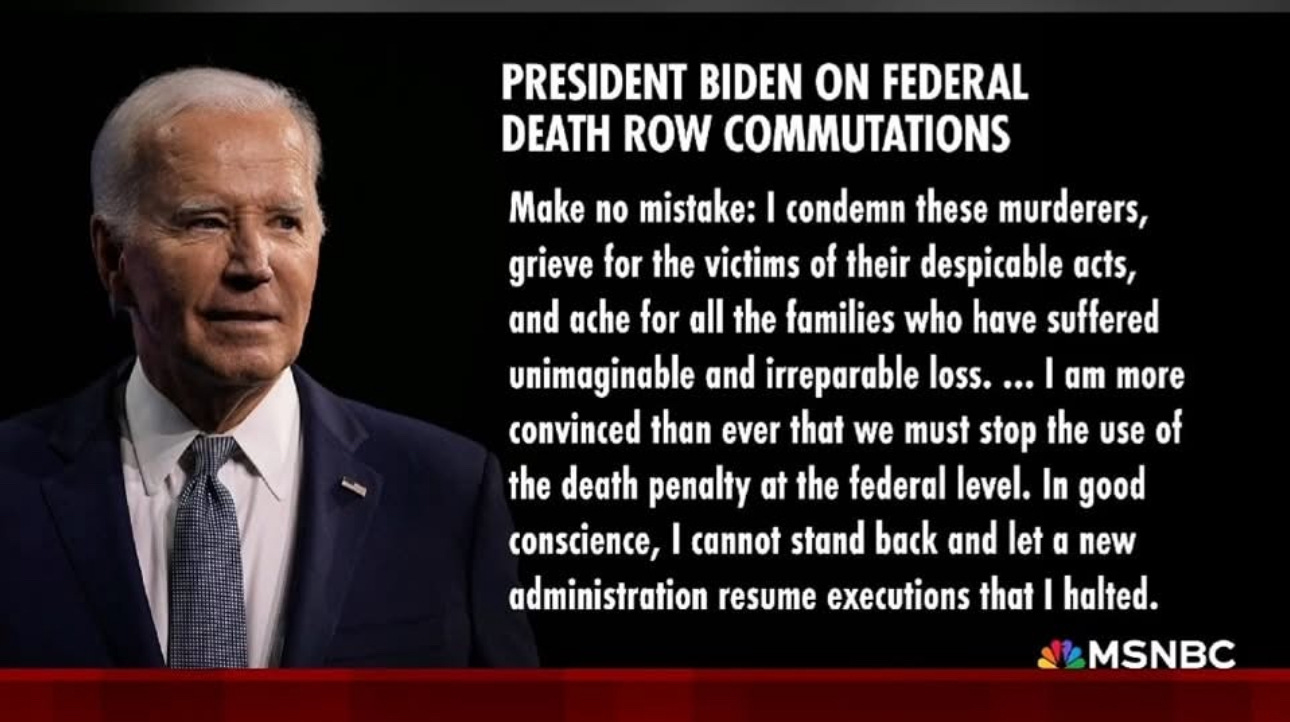

President Biden will be praised by many who have spent decades opposing the brutality of state-sanctioned killing. Others will condemn him for showing mercy to those who have taken lives. Many of his critics will claim to serve a God who values mercy, redemption, and respect for the sanctity of life yet demands vengeance.

I understand the desire for retribution. I’ve felt it myself. In that mall in the ’80s, when I snatched that girl up by her neck, I did not care about a preponderance of evidence. I did not investigate if it was premeditated or accidental or if she was pushed into my mom. I can’t even be certain it was her and not her friend ahead of her. I reacted out of fear and anger, and I am grateful that I inflicted no real physical harm.

I understand the desire for swift and terrible retribution. Which action movie or thriller doesn’t reinforce this idea over and over and over again?

Justice is not about what satisfies our pain or anger—it’s about what elevates us as a society.

The death penalty denies us the opportunity to rise above our darkest impulses. It hardens our system into one that mirrors the violence we claim to abhor.